Donaghmore in Penal Times

See also: Donaghmore

A Glimpse of Navan and Donaghmore in Penal Times

By Vincent Mulvany

______________________________

On the 3rd October 1691 the Williamite Wars came to an end with the signing of the Treaty of Limerick, which guaranteed Catholics the right to practice their religion.

However, between 1695 and 1728, the Treaty’s first article was completely ignored by the Irish Parliament when it enacted what came to be called the ‘Popery Code’ or Penal Law. Under this harsh penal code, Catholics were prohibited from practising their faith, buying or inheriting land, educating their children, bearing arms, owning property and becoming members of Parliament or the professions. In 1728, they were denied the vote. The objective of the Penal Code was to keep Catholics in a position of utter inferiority, and political, social and economic subjugation.[1]

The section of Railway St., in Navan which leads to Leighsbrook was once known as Chapel Lane. It was named after a little mudwall chapel which stood by the stream there during penal times. In the early years of Queen Anne (1702 – 1714), in the words of Dean Cogan:

… a little mudwall chapel was erected at Leighsbrook, separated from Leighsbrook House the present residence of the Sisters of Mercy, by a stream. In this humble temple the Catholics of Navan worshiped God for seventy years, and frequently during this time, their little chapel was closed against them, owing to a more rigorous enforcement of the penal laws, and Mass would be celebrated by stealth, while the stars were twinkling, on the lonely rocks which line the Boyne below Blackcastle.’[2]

We get a passing glimpse of this little chapel in the mid - 18th century from an account of a visit to Navan by Arthur O’Neill a noted Irish harper. He mentions the interesting custom if the harp being played there at the Masses on Christmas day.[3] One Christmas night around 1772, the little chapel crumbled and fell, and the Catholics of Navan once again found themselves without a place to worship.[4]

Fig.1 The stream at Leighsbrook (before it was culverted), where the little mudwall chapel stood.

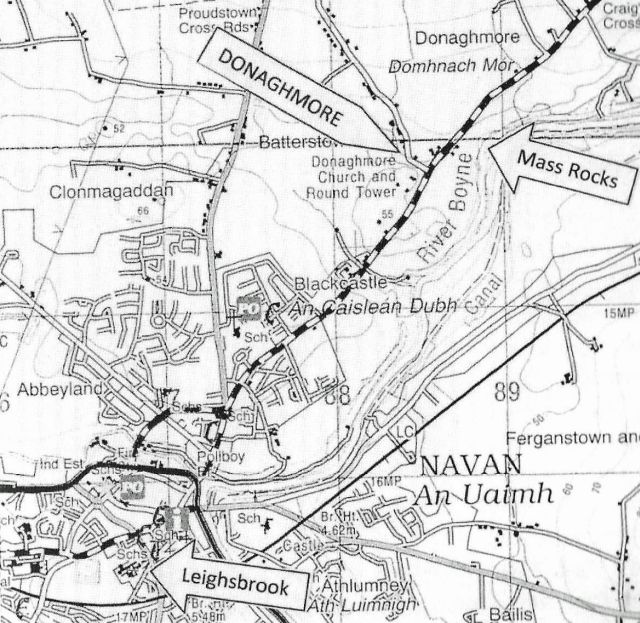

About 1.5 kms NE of Navan lies the early monastic site of Donaghmore, which consists of the Round Tower, the 13th century church and its adjoining graveyard. Opposite this, between the River Boyne and the road to Slane, Blackcastle demesne forms a narrow strip of land which runs from Navan to the townland of Dunmoe.

A steep, rocky and wooded embankment descends from here to the river bank. On a level piece of land between thisand the river’s edge lie two circular holes.

It is believed that these two rocks are the ones mentioned by Dean Cogan in the extract quoted above. Above them in the rocky undergrowth is the entrance to a small cave that may have been used as a place of shelter or sanctuary during the penal times (see Fig.2).

Fig. 2 Cave at Donaghmore

Figs. 3 View of the Mass Rock from the Rampart walk, and Fig.4 (right) in close up

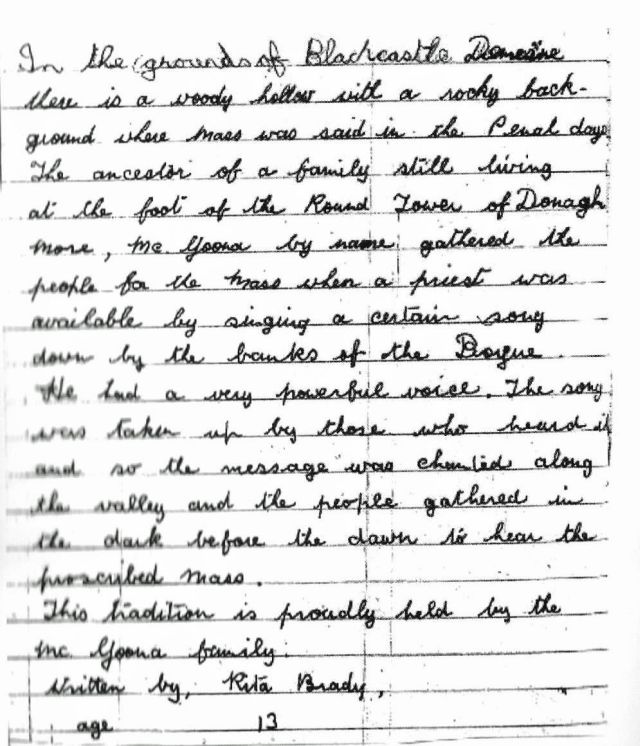

For the 1937-8 Schools’ Manuscript Collection, Rita Brady, then a 13 year old pupil of Loreto in Navan, collected the following from the McGoona family of Donaghmore.[5]

Fig. 5 From the Schools' Manuscript Collection

Fig. 5 From the Schools' Manuscript Collection

Fig. 6 Map showing locations of places mentioned in the text

The Priest Hunter was a person, who, acting on behalf of parliament, spied on, or captured Catholic priests during Penal times. Some were criminals, forced into the position by the authorities, and some others were volunteers, experienced soldiers and former spies. They recruited informants from within the Catholic communities, and gathered information on the movements of fugitive priests, and the times and places where prohibited Mass would be celebrated at night time on the Mass Rocks. The rewards were substantial. The bounty paid for a captured bishop ranged from £50 – £100 and for a priest £10 - £20. To avoid detection, some attending priests wore a veil in order to protect their flock from being questioned, as to who celebrated the Mass.[6]

A Memory of Penal Days

The following are the words of Winnie McGoona recorded in 1966.

Fig. 7 (right) Winifred McGoona

In the days of the priest hunters, Mass was sometime celebrated secretly along the River Boyne, not far from here, (Donaghmore). My grandfather told my mother of the method used to collect the people; his grand uncles Thomas, Patrick, and James McGoona would take up their places along the river and under pretence of gathering firewood, or looking for foxes, or setting snares for rabbits, they would start singing. The running water would carry their voices down the river, and people would begin to collect, usually one or two would come to represent a family. They might sometimes be waiting a week, with oaten cakes for food. The priest would come in disguise, but sometimes if an informer gave the game away, he might have to go before Mass was finished. I told this family legend to Mother Columba many years ago, and she used it as the subject of a school play in Irish, which was, I believe, produced at the Schools' Festival in Dublin. [7]

The McGoonas lived in a unique 200 year old farmhouse, built in the traditional Irish style on elevated ground beside the monastic settlement of Donaghmore. Beyond the house was a 5 acre fruit farm of cherry and apple trees.[8]

In July 1996 I met Winifred (Winnie) McGoona for the first time, along with some of her family members. She passed away in October later that same year. During the course of the conversation she related very vividly the family tradition about John McGoona during Penal times. What struck me forcibly was the unbroken line of the oral tradition handed down to her and the richness in the detail. The story has always intrigued me, and the following notes recorded that July evening give us some idea of where the Penal days Mass was celebrated ‘on the lonely rocks which line the Boyne below Blackcastle.’

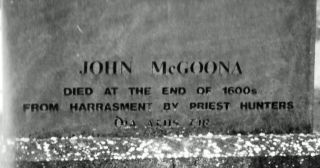

Winnie spoke of an early relative who is buried in Donaghmore Graveyard. ‘In the 17th century religion and saying Mass was forbidden. The military and priest hunters sought out any meetings where there might be Masses said. John McGoona had a good singing voice and summoned the people to mass along the Boyne opposite Donaghmore by the river carrying his voice – later Mass would be celebrated by the priest. When he was sought by the priest hunters he would submerge himself in the river to avoid being caught. He died at an early age from consumption (tuberculosis) beside a tree in the orchard near the house, known as ‘John’s corner’.’[9]

The inscription at the base of the McGoona family headstone in Donaghmore Graveyard is illustrated below (Fig. 8)

Fig. 8 Donaghmore Graveyard

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank Martin Dier for putting the last piece of this research into place by drawing my attention to the Mass Rocks at Donaghmore and also for the use of his photographs. I would also especially like to thank Ethna Cantwell for all her help and encouragement in bringing this article to a successful conclusion.

[1] Seán Duffy, The Concise History of Ireland, (Dublin 2000), p. 121

[2] Dean Cogan, The History of the Diocese of Meath Ancient and Modern, Vol. 1, pp.231-2.

[3] Cogan, p. 232.

[4] John Brady, A short history of the Parishes of Meath 1867-1937, p.962.

[5] Schools’ Manuscript Collection 1937-8 Clochar Loreto Navan, Sr. M. Colm, Folio 700, p. 166 (Irish Folklore Commission)

[6] Thomas D’Arcy McGee, The Priest Hunter: A tale of the Irish Penal Laws (1844)

[7] Ríocht na Midhe, Journal of the Meath Archaelogical & Historical Society, Vol. 3, no. 4, 1966, p. 389

[8] Alice Curtayne, Francis Ledwidge – A life of the Poet, 1972, p. 38

[9] Notes taken by Vincent Mulvany in conversation with Miss Winnie McGoona, July 1996.